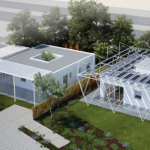

The world of finance is associated with Wall Street, opulence, and excess, so it was a notable decision that finance big shots Linda Yates and Paul Holland would build a house to meet incredibly high conservationist expectations. The resulting house in Portoal Vallley, CA, dubbed Tah Mah Lah, takes its name from the Native American Ohlone word for “mountain lion,” a nod to the project’s dedication to native plants and materials and its veneration for the prehistory of the land on which it was built.

This gorgeous residence was constructed almost entirely of salvaged materials. Wood from old, local barns and a 102-year-old granary was used to create its recycled steel roof, hand railings, kitchen hood, salvaged-limestone fireplaces, and floors. Any material that could not be found salvaged was created of cedar, harvested from woods that were certified by the Forest Stewardship Council, an organization that seeks to promote responsible usage of woodland resources. In addition, the owners made sure that no paints or fossil fuels were used in the construction process.

Upon completion in 2011, the net-zero-energy, zero-carbon-emission earned the highest LEED rating for a custom home of its size, acquiring the title “The Greenest Home in America.” Though it has since been bumped out of first place, the home remains an exemplary conservationist structure with impressive features.

Though the amply funded, 5,600 square foot Tah.Mah.Lah. remains a bit out of fiscal reach for most conservationist home-owners, the ideas, strategies, and technologies in place could be practical for most conservationally-minded homes. These considerations include:

- An underground cistern that collects up to 50,000 gallons of rainwater;

- Grey water and black water recycling—channeling them into irrigation and fertilization of the property’s lush, native grasses;

- Geothermal underfloor heating;

- Solar energy;

- A sustainably built pool and willow-weed playhouse designed by Australian artist Patrick Dougherty;

- A Control4 monitoring system that can be set to manage the above as well as perform a multitude of energy-saving tasks automatically;

- Movement sensors that turn lights on and off as occupants move throughout the rooms.

The home is not only passive, but it also succeeds in being a bit restorative as well. The over-four-dozen artists, engineers, energy specialists, and wildlife biologists served as consultants for the home that the press release says, “generates more energy than it uses, rebuilds habitat, saves and repurposes water, and reduces and reuses waste.”

As part of the press release, Yates beams with pride as she explains that the home goes beyond energy independence as it also restores some of the native land; it “fits seamlessly into the ecosystem and restores the land as if it were 200 years ago.” This impressive feat proves that even a luxurious home with a giant physical footprint can be designed to not only sustain itself, but to reduce its impact on the environment as well as restoring its surroundings.

“It’s not about a checklist; it’s about changing the way we think from beginning to end and beyond,” says Michael Booth, the interior architect. Yates agrees. “Tah.Mah.Lah. is just a pebble in the pond that we hope creates a ripple,” she says. Hopefully, she is right. Perhaps those opulent showman in our country as well as those wanting to make a difference in the world will take note.

Until more homes like it crop up, Tah.Mah.Lah. reigns supreme for a home of its size and budget; luxury does not have to be wasteful, and sustainable can easily stretch into restorative if we can change the way we think. (Images: nahb.org and tahmahlah.com)

Eichler Inspired Modular Homes that Can be Customized to Anyone’s Taste

Eichler Inspired Modular Homes that Can be Customized to Anyone’s Taste Qatar is Building First Passive House Project but is There Hidden Agenda Behind It?

Qatar is Building First Passive House Project but is There Hidden Agenda Behind It? Honda is Unleashing the Tech in its Net Zero Energy ‘Smart Home’

Honda is Unleashing the Tech in its Net Zero Energy ‘Smart Home’